Relentless Repetition: Michael Hong’s search for self in Oi-ee Moo-chim

Michael Hong was attempting to recreate a cucumber dish that his mom had been making for him all his life. The dish seemed simple enough, but even with her recipe, and after many attempts, he just couldn’t get it right.

That’s when it hit him: He was missing his mother’s son-maat, the Korean concept of hand-flavor. “It’s this idea that there’s an indescribable flavor that comes from the hand—a lot of times rooted in the love and affection that the person who is cooking has for the person who will eat,” Hong says. Hand-flavor is passed down from generation to generation, often along maternal lines.

The connection to his art-making was an immediate aha! When Hong works with clay, he’s constantly engaged in tactile feedback with the material; he responds to the clay, and the clay responds to him. This, too, was hand-flavor. “I was thinking about this bodily relationship that I have with the clay,” he explains. “The exchange that happens as I interact with it must be my hand-flavor coming out.”

He knew what hand-flavor tasted like, but what did it look like? Hong brought that question into his studio and began to investigate. Over time, the question evolved, and he started to ask himself, where does my hand-flavor come from? The work he was making became an exploration of his own identity and the forces that shaped him.

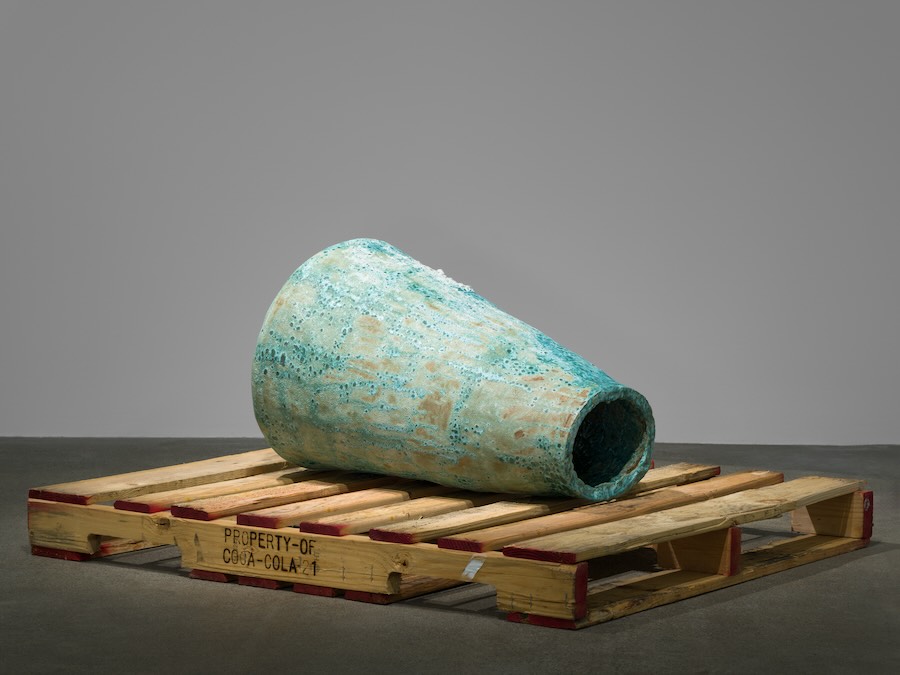

The results of this research are currently on view in Hong’s Gallery 4Culture exhibition, Oi-ee Moo-chim, which takes its name from the Korean cucumber dish that first set it in motion. The exhibition features a series of abstract self-portraits as well as a series of pots that reference traditional Korean fermentation vessels called hangari. The artworks in the show also incorporate familiar household items that Hong remembers from his youth, like rice bags, pepper flakes, work gloves, and yarn.

Hong grew up in Koreatown, Los Angeles, a three-square-mile neighborhood dense with Korean and Korean American people and traditions. He and his two brothers were raised by their single mother, an immigrant, who worked hard to keep the family afloat.

“I never really see her take a break,” Hong says. “If she does take a break, it’s always with TV on in the background while she’s doing something else. Especially with cooking, she’s always going the long way with the time and work she puts into it. It’s like a way of saying ‘I love you.’”

Reflecting on his mother’s effort offered Hong a way to consider and embrace his own ferocious work ethic. He sees her constant activity as a coping mechanism, a way of escaping the uncertainties of life. “There’s a lot of similarities between being a single mother, raising three kids and me just living with my own uncertainties,” he says.

The self-portraits in Oi-ee Moo-chim began with Hong thinking about the physical space he occupies with his body. They all start at the base with his footprint and build to his 6-foot height by repeating a small pinching motion over and over again. The repetition creates a texture Hong calls “dumpling skin” and they require a ton of labor. “It’s out of that repetition and monotony that I’m trying to visually articulate hand-flavor,” he says.

These works arrived at their shape organically as Hong focused on his dialogue with the clay itself and “let it do its thing.” As he built it up, the forms reflected how his body was moving with the material, working to keep it from collapsing. Twenty of them collapsed along the way. In the finished pieces, he says, “I can see my arm sort of having gone through these openings or how I was trying to balance this piece so that I wouldn’t tip over.” To him, those openings resemble portals or gates for him to pass through as he seeks to understand himself.

With the earlier pieces, his mark makings show more irregularities and more of his physical presence, but the later ones become increasingly consistent and uniform. The older portraits took Hong a long time to make, but he increased his speed with practice. “Now I can probably get one up in two days,” he says, a pace he chalks up to the impatience he inherited from his mother.

The vessels in Oi-ee Moo-chim are inspired by the Korean pots that are used to ferment foods and store all sorts of things. On the outside, they look ordinary, but on the inside, they’re covered in the same dumpling skin as the self-portraits. “They’re an inside-out conversation,” Hong says, pointing out that these pots are meant to nurture or hide whatever’s inside them. “So, what am I hiding?” he wondered.

All sorts of things, it turns out, whether serious, funny, or both. He recalled some of his mom’s “weird rituals,” like hiding soda and junk food from Hong and his brothers by stashing them in the pots where they were unlikely to look. Those rituals inspired him to figure out ways he could similarly repurpose household items in ways that might not exactly make sense. One pot has a tiny video inside that shows Hong making his marks in the clay and plays audio from the reality show Love Island, a series he often listened to while working; it’s an homage to the TV shows his mom always had on in the background. Another pot features smells that recall the kimchi and soybean paste lunches she packed him for school.

As for the quest to find out what his hand-flavor reveals? “I’ve been looking so deep within myself, I think I’m at a point where I don’t know where I am. Am I who I am right now? How much of that is my old self?” Like his towering self-portraits, the answers build on themselves.

Oi-ee Moo-chim is on view at Gallery 4Culture through Oct. 31.